15th August, 2025 in Military

Reflections of War is a captivating anthology showcasing 150 rare images from the Second World War. This recently discovered archive of original press negatives has been thoughtfully restored, and the accompanying press notes meticulously researched, to reveal compellin…

14th August, 2025 in Military, Women in History

Bletchley Park is perceived as a world of male intellectuals supported by a vast staff of women in menial roles – a place where men helped sway the course of the Second World War. But women were not just typists and clerks. They had serious, full-on codebreaking roles. And not ju…

13th August, 2025 in Local & Family History

England is a country which, despite its relatively small size, has a long, varied and colourful history, and much of this can still be seen and understood if you know where to look. Each of its villages, towns and cities has its own tales to tell, and the area generally known as…

13th August, 2025 in Folklore, Local & Family History

Wales holds in the popular imagination a reputation of magic, mystery, and ancient ways. A land apart from its’ neighbours, Cymru has been a destination for centuries, but more importantly it is home to a proud culture. Yet, despite the richness of its’ heritage, only certain asp…

29th May, 2025 in Maritime, Military

Since the mid 1800s a number of Cunard ships have been requisitioned to support Britain during wartime. Several Cunarders were requisitioned to support Britain during the Crimean War (1853–56). A total of fourteen Cunard ships served in the campaign. Of those, Arabia transported…

16th April, 2025 in History, Military, Society & Culture

In his book Under Fire, Stephen Bourne draws on first-hand testimonies to tell the whole story of Britain’s black community during the Second World War, shedding light on an oft neglected area of history. Drawing on a wealth of experiences from evacuees to entertainers, gove…

28th January, 2025 in Local & Family History

According to the make-it-up-as-you-go-along 12th-century historian Geoffrey of Monmouth, the River Humber was named after Humber, the King of the Huns. Learn more behind the history of Humber Crossing from Paul Sullivan author of new book The Little History of Lincolnshire. The w…

22nd January, 2025 in Local & Family History, Maritime

When fishing boats were numerous, Scotland was a wonderful place to see them. Even now, it’s still possible to catch a hint of what used to be. Peter Drummond has roamed the coastlines and harbours of Scotland for over thirty years, always with his trusty camera in hand. Although…

20th January, 2025 in Biography & Memoir, Military

‘Before leaving, we were issued with rations for about two and half days. The weather was terrible, and very, very cold. We arrived at a place called Winterveldt. We had covered a distance of about twenty miles and our resting place was a barn with cold floors, with just a bit of…

7th January, 2025 in Local & Family History

If you’re ever walking along Corporation Street in Birmingham on a busy afternoon just stop and look around you. Listen to the noise, the chattering of voices, the distant hum of traffic, then close your eyes. When you open them again imagine you have been whisked away in a time…

5th December, 2024 in Local & Family History, Military, Women in History

John Lander author of new book Don’t Delay – Enrol Today highlights the importance of the women’s land army in Hampshire during both World Wars. World War I The Women’s Land Army was established by the British government to recruit women and girls to work in Britain’s agriculture…

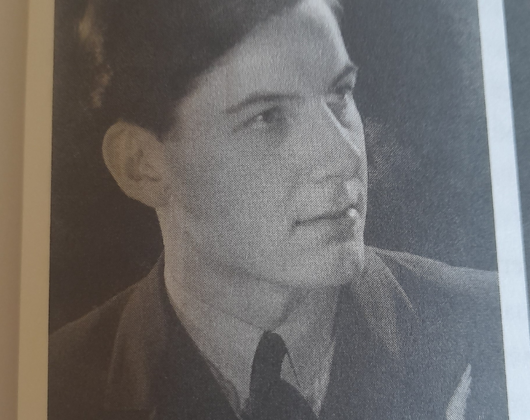

19th September, 2024 in Aviation, Biography & Memoir, Military

In 1934, aged just 16, Louis Hagen was sent to Lichtenberg concentration camp after being betrayed for an off-hand joke by a Nazi-sympathising family maid. Mercifully, his time there was cut short thanks to the intervention of a school friend’s father, and he escaped to the UK so…

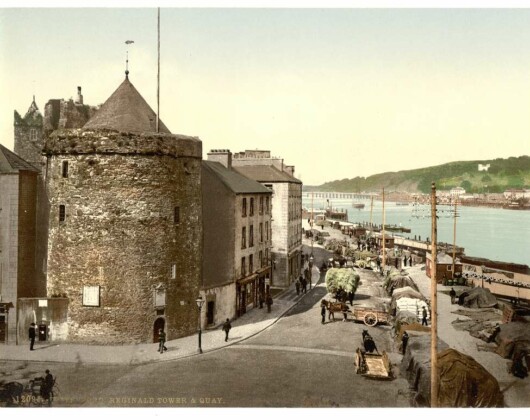

12th September, 2024 in Local & Family History, Sport

Cian Manning author of ‘I Love Me County’ provides a brief history of Waterford and its legacy. The Gentle County, Waterford, can boast a proud sporting tradition. It is as long as it is varied. It’s largest urban area, Waterford City, has witnessed bull-baiting at Ballybricken t…

10th September, 2024 in Local & Family History, Military

The Royal Hospital Chelsea as a home for old soldiers has always been associated with warfare. The Second World War however represents a unique chapter in the history of the institution as the Hospital itself was in the line of fire for a sustained period. Casualties amongst the…

2nd September, 2024 in Military, Society & Culture

Eighty-five years ago, the outbreak of the Second World War was confirmed. Author Victoria Panton Bacon asks, what have we learnt? Colin Bell, now 103, recollects the announcement of the Second World War. Colin was 18 years old at the time, living with his family in East Molesey…

12th August, 2024 in Archaeology, Local & Family History

Northumberland has more castles, fortalices, towers, peles, bastles and barmkins than any other county in the British Isles. Castles of all periods were the private residences and fortresses of kings and noblemen. Read an extract from the new book Castles and Strongholds of North…

15th July, 2024 in Local & Family History

Bracknell is one of the post war New Towns so you would be forgiven for thinking there is no history to the settlement. Bracknell’s history is unique. Author Andrew Radgick author of The Story of Bracknell discusses the history behind this new town. Early traces of people in the…

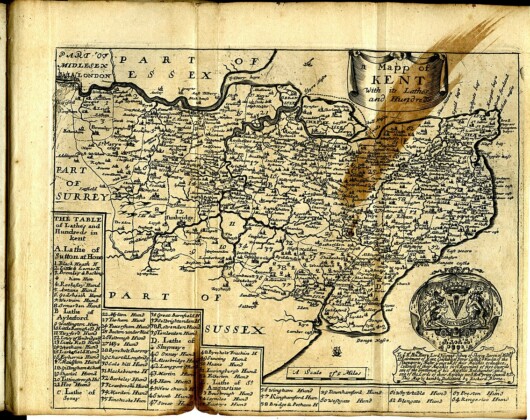

9th July, 2024 in Local & Family History

Kent truly is the gateway into England and the whole of the history of this “Sceptred Isle” has passed through the ancient kingdom of Kent. Its very name goes back into the mists of time. A Greek traveller who sailed the Channel twenty four centuries ago recorded in his records t…

13th June, 2024 in Archaeology, Local & Family History

Dr. Oliver Taylor author of the new book Bath Abbey’s Monuments: An Illustrated History tells the full story of Bath Abbey’s monuments for the first time and highlights the significance of the collection. By the beginning of the 1800s, Bath had one of the largest populations in B…

11th June, 2024 in History, Local & Family History

Our national history helps shape our personal identity, but history does not accrete like permanent stratigraphic layers. Serendipitous research can sometimes shatter received assumptions, and we may find that we are not quite the product of a past that was taught to us. Chris Bu…

5th June, 2024 in Biography & Memoir, Military

‘Good God!’ I thought after being shown a map with a small area on it that we had taken back, ‘We’ve just taken part in D-Day!’ Flight Lieutenant Noble Frankland (DFC CB CBE) is one of those for whom 6th June 1944 might have been just another ‘ordinary day’ in the operational c…

5th June, 2024 in Military, Women in History

‘I remember one particularly badly injured pilot amongst the others being brought in. Because of his multiple injuries he was taken straight to the consultant surgeon for examination and treatment, but he was still conscious as he was taken to surgery. There was nothing anyone co…

29th May, 2024 in Local & Family History

I tend to think of Derbyshire’s landscape as a beautiful patchwork quilt stitched together by its dry-stone walls. The fabric of the past may be reused or altered but look closely and traces of the people and cultures who have lived here for thousands of years are still visible….

14th May, 2024 in Local & Family History, Natural World

East Anglia is known for its fabulous coastline and riverside cities such as Cambridge and Norwich. The countryside in between is all-too-often dismissed as being flat and featureless. While ‘hill’ is a relative term in Cambridgeshire and Norfolk, the rural landscape is certainly…

22nd April, 2024 in Military, Society & Culture

The thought arrived as I was hovering inside a crowded coffee shop directly opposite the Royal Courts of Justice on the Strand. Tables and bars pulsed with suited, brief cased, device-bashing professionals; the buzz from conversation being shouted and spoken into phones and faces…

3rd April, 2024 in Military

And so, in the early morning of 11 May, 973 heavy bombers took off in fine weather from airfields across East Anglia. Their mission was Operation 350: to fly 500 miles across France to attack railway marshalling yards in Mulhouse, Épinal, Belfort and Chaumont, and an airfield at…

13th March, 2024 in Local & Family History

Authors Colin and Elizabeth give us the back story of how they collected the photographs for their new book The Lost Back-to-Back Streets of Leeds: Woodhouse in the 1960s and 70s. Featuring nearly 140 of those photographs in black and white, plus some 30 more in full colour. We h…

19th January, 2024 in Local & Family History, Transport & Industry, Women in History

This is the last book in the trilogy that started with my great great grandmother, Hannah Hall in the 1820’s as she re-located with her family to a new coal mine opening up in Hetton-le-Hole, County Durham. No-one at that time could have known the importance of that move. By 1822…

15th January, 2024 in Military, Women in History

Author of Remarkable Women of the Second World War, Victoria Panton Bacon, remembers Pat Rorke. Pat died on 9th December 2023, aged 100 years and five weeks. ‘After the war, you have to learn to live together, remember that you are all human … behind all the bare recounted facts…

6th December, 2023 in Local & Family History

Roger Stephens author of The Little Book of Cheshire provides some interesting historical facts about the county of Cheshire, for those who are residents or tourists visiting the area! It seemed too good to be true; a chance to get on a soap box and sing the praises of one’s hom…