14th August, 2025 in Military, Women in History

By Dermot Turing

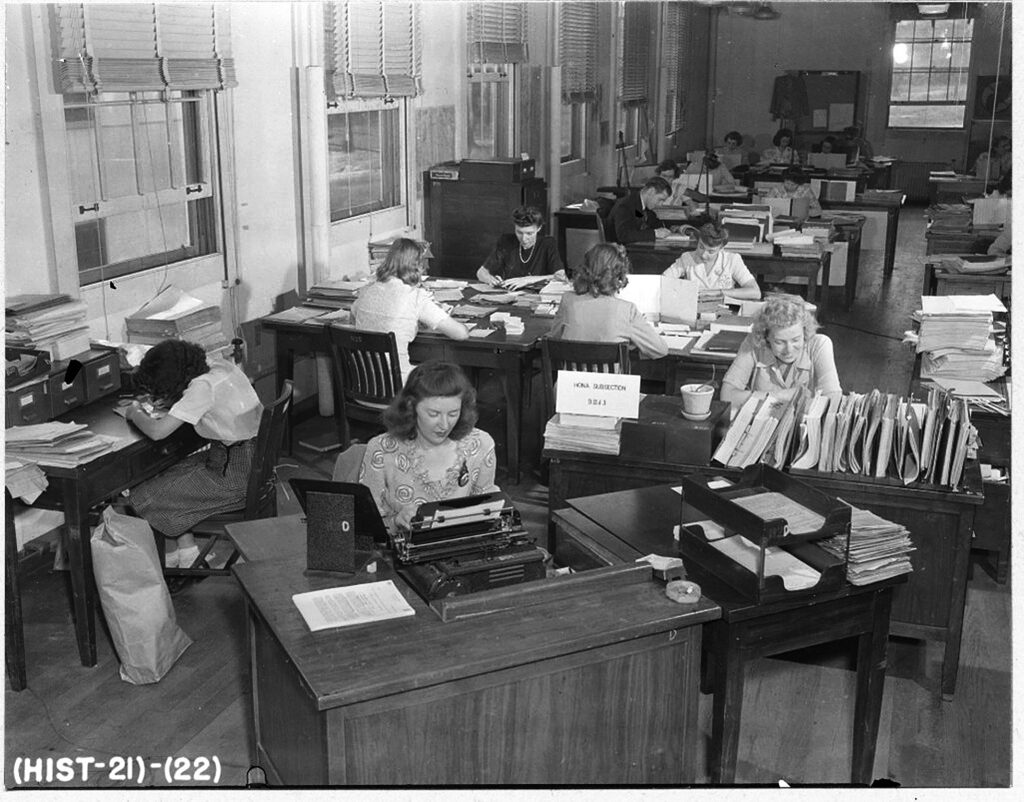

It’s right that, by the end of the war, 75% of Bletchley’s staff were women. But in the years since the story of Bletchley Park became declassified, we have been led to understand that the women of Bletchley were largely employed in junior, menial roles. We know of vast squadrons of Wrens who operated Bombe machines to help solve Enigma, women in the WAAF and the ATS, and an anonymous group of women civilians notionally employed by the Foreign Office who seemed to be deployed on non-specific clerical work like ‘indexing’. The codebreaking, by contrast, was done by men, notably people like Alan Turing, who were hired at the beginning of the war from an ‘Emergency List’ compiled by the head of the Government Code & Cypher School (which became Bletchley Park and then GCHQ), Alastair Denniston. Denniston described these people as ‘men of the professor type’. So, the accepted story is that the male professors did the brainy stuff and the women did the low-skilled tasks.

My book is about whether that’s true. There were, indeed, women doing codebreaking. But were they exceptions? And why didn’t we know about them before?

In fact, looking at the records – things like official reports in the archives and oral histories – it turns out that there were dozens of women doing full-on codebreaking roles. Right from the outset, when the GC&CS was formed in 1919, women were entrusted with professional codebreaking jobs. This didn’t change when the Second World War began. Rather the reverse: there was a big recruitment drive, particularly across women’s colleges in Cambridge and Oxford, to bring in women with the right skills.

Again there’s a myth here about women at Bletchley Park. Setting aside the women in uniform, who were recruited rather later in the war, the picture we have been shown is one of very posh young women – the ‘Debs’ who were presented at court and who had connections in high places. Because they were upper-crust they could be relied on to keep a secret. Then when they got to Bletchley they were given filing and tea-making to do. I don’t deny that there were a handful of these posh ladies there (and some of them did rather more important things than pouring the tea) but the main cohort of civilian recruits came as a result of a call to the colleges and a fairly stern selection process conducted by a lady called Miss Moore at the Foreign Office.

One of my favourites is a lady called Wendy White, who appears in the archives as a ‘superintendent of typists’. She was a veteran of the First World War, kept on when the GC&CS was formed in 1919. She worked in the Naval Section and was the only woman among an irreverent group of men who did the same work. It’s clear from the papers that she was quite able to hold her own, and it’s also clear that she was recognised as a capable codebreaker. Things only went wrong in the Second World War, when there was this influx of ‘men of the professor type’, who didn’t like to be told by someone graded as a superintendent of typists that their work didn’t stack up.

Then there’s the woman who put the post-Watergate Church committee in its place. That was Juanita Moody, who had given the White House an early warning on the Cuban missiles, and then found herself put up as the fall-guy when the NSA was being accused of spying on its own citizens in the 1970s. But she hit back hard. She was a tough nut, most impressive.

And I was quite astonished to find out about a German codebreaker called Erika Pannwitz. She was a mathematician who broke American State Department signals during the Second World War. She was a bit of a stand-out because she dressed in men’s clothing, which seems to have been okay in Nazi times (rather surprisingly) but then the university authorities took against her after the war, and she was denied the academic post she craved. It’s odd that the post-war environment was more hostile than the regime which we thought was completely inimical to unfeminine women. There were surprises everywhere in this exploration!

That’s the big question, and it has many answers.

The starting-point is that phrase of Commander Denniston’s – the ‘men of the professor type’. That comes from a file in the National Archives which details his efforts at pre-war recruitment. All those dons from Cambridge and Oxford were taken on as ‘senior assistants’, which meant senior-rank codebreakers, and all the women he recruited were classified as ‘linguists’ or ‘clerical staff’ or even ‘typists’. When historians read these papers they take things at face value. But what’s not obvious, until you dive into it, is that the job titles are not job descriptions. Women’s job titles were different, because they were paid on different scales. To fill the urgent need for more codebreakers, women were taken on as codebreakers, but the job titles they had were completely misleading.

My favourite story to illustrate this was told by Joan Clarke herself. In order to get herself promoted she needed to become a ‘linguist’, even though she was a mathematician working on the naval Enigma problem. She had to fill in a form which required her to list her language skills, and she put ‘None’. Needless to say she got the promotion. But it showed what a nonsense the job-labels were, relative to the work the women were actually doing.

A number of factors come into play. First of all, when the Bletchley story was first declassified, all the books were written by men and many of them were about what they, the men, had done. Some were about the ‘notable people’ at Bletchley, some of whom were famous in the post-war era for other things, and some of them were about the people in leadership roles at Bletchley, and as is the way of things the leaders get the credit for everything done in their section even if they themselves don’t wield the tools.

More recently, we have heard the wonderful first-hand stories of women who worked at Bletchley. Typically, of course, these are stories of those who were very young when they worked there, so they were genuinely in junior roles – and their stories got told because they are still here. It’s a rich and colourful collection and we are privileged to have these veterans around to tell them. But the women who actually worked in codebreaking roles during the Second World War were a bit older, so didn’t live to describe their work. Their witness record is more threadbare. It’s a shame, because it reinforces the stereotype that women were only allowed to work on lower-grade things. Perhaps we should say that young people fresh out of school were put to work in junior roles, then it comes into a better perspective.

Some years ago I read a very interesting short paper by Karen Lewis, who volunteers at Bletchley Park. It was called ‘Women of the Linguist Type’ – which was a wry take on that old phrase of Commander Denniston’s. Karen’s paper showed that Denniston had been hiring women from Oxbridge as well, who were taken on as what were called ‘linguists’.

Well, that idea sort of floated about in the back of my mind, but then I kept coming across more and more stories of women who hadn’t been doing menial roles at Bletchley, and I thought I would cross-check in the archives about how they were described.

And it turned out that it wasn’t just Joan Clarke. All sorts of codebreaker women had been classified as ‘linguists’ and also as typists and clerks and what-have-you, because these were the lower-paid job strata where only women were employed. For example, there was Helen Haselden, who was officially an ‘established typist’ but whose job was to reconstruct the ‘subtractor tables’ used by the Spanish to encipher their signals. And Rhoda Welsford, a veteran of the First World War, called back to break codes again in the Naval Section, who was graded as a ‘clerical officer’.

So a piece of curiosity about terminology led to a lot of research about women’s position in the civil service and a wider enquiry about why nobody seemed to have noticed that women at Bletchley did have professional jobs.

My previous book, which was about the weakness of British codes during the Second World War, involved a lot of research into the efforts of the German codebreaking agencies to master the British systems. In that work I came across the most extraordinary thing: in the heart of Ribbentrop’s Foreign Office in Berlin there was a cohort of women codebreakers. This was the Nazi regime where women had all been fired from professional civil service positions after Hitler came to power. So these women were very interesting, if peripheral to my previous book, and I wanted to look into their stories further.

It’s very curious how there were parallels with the Bletchley Park system, for example in the way that job labels didn’t match the actual work being done. And there were other parallels: for example, in the way that the American codebreaking agencies hired wartime codebreaking staff – huge numbers of young women graduates taken on just like at Bletchley Park.

And then the story got even more interesting: in the United States, modern codebreaking really began – at the time of the First World War – with the work of two women, Elizebeth Friedman and Agnes Driscoll. Mrs Driscoll became the chief codebreaker of the U.S. Navy and Mrs Friedman the main intelligence source acting as a gang-buster in the prohibition era. And yet, even in the U.S., the principal codebreaking stories have usually featured men as the heroes. It seemed that women disappearing from codebreaking history was a world-wide phenomenon, not just a curiosity of Bletchley Park.

So this opened up some different enquiries, comparing what happened in different countries, things like the marriage bar and the attitude to sexual preferences and how things like that affected employability in sensitive jobs.

I think one of the biggest shocks was seeing how one of the famous American codebreakers – a man – had completely panned the reputation of Agnes Driscoll, who not only founded American naval codebreaking but had a string of very important code-breaking successes to her credit. For some reason this guy had taken against Mrs Driscoll and, when he came to give an oral history interview in his retirement years he let all the poison flow out. He shredded her abilities as a codebreaker and his opinion of her personality was about as negative as you can get.

But the problem was that other witnesses didn’t agree with any of it. The real issue to my mind is why this particular person in his interview had been treated with such reverence and not challenged on anything he said. It might not have mattered except that his view somehow crystallised into the received historical view, and it’s wrong, and unfair – and it tells you quite a lot about how history comes to get accepted. I learned a lot from that. You have to be very critical about your sources and the context in which they say the things they say.

You might sum it up this way: a central theme of my book is about how the archival record was misinterpreted, because historians took too literally what they read, rather than looking into the context. It’s how we failed to see the women codebreakers who were there, in the record, right before our eyes.

Books related to this article