16th April, 2025 in History, Military, Society & Culture

By Stephen Bourne

Tuesday, 8 May 1945 was VE – Victory in Europe – Day. Germany had surrendered. It was the end of the war in Europe. It was a time for celebration, but it was also a time for reflection. On VE Day, a jubilant crowd of thousands made their way to Buckingham Palace in London. They clamoured for the royal family. King George VI and Queen Elizabeth, with the two princesses, Elizabeth and Margaret, went out on the palace balcony eight times. Prime Minister Winston Churchill joined the royal family on the balcony. That day he told the nation:

‘My dear friends, this is your hour. This is not victory of a party or of any class. It’s a victory of the great British nation as a whole.’

Winston Churchill, VE Day 8 May 1945

Far away in Germany, Adelaide Hall was in the middle of her ENSA tour. She was in Hamburg when she was notified that the war had ended. Adelaide then became one of the first entertainers to arrive in Berlin to congratulate the troops after the city had been liberated. She said:

‘There was not a street in sight – nothing. They had all been razed to the ground, and people were putting up little boards, made from bits of wood, to identify the names of the streets that used to be there.’

Adelaide Hall

After the war, her husband Bert couldn’t get her out of the uniform specially made for her by Madame Adele of Grosvenor Street. He told his wife, ‘The war is over now, honey, you can let that uniform go!’

Norma Best, from British Honduras, had joined the ATS in 1944. She was in London for VE Day and took part in the endof-war celebrations on the Embankment. She later reflected:

‘I think the spirit of the war was that we were all fighting to win. All we could think about is to get in there, do a good job, let’s get it over and done with. Colour didn’t come into it.’

Norma Best

In January 1945, the newsletter of the LCP [League of Coloured Peoples] noted that Ulric Cross had been appointed the first liaison officer for West Indians in the RAF. They added that the recent award of the Distinguished Service Order (DSO) to Ulric was ‘a joy to every West Indian heart’. Ulric heard on the radio that the war was over, and he went to Piccadilly Circus in London to join the celebrations:

‘Everybody was overjoyed and I just didn’t feel like taking any part in it. So I went back home. I just felt that a lot of people had been killed. This was not a cause for celebration. The war did not stop people from being killed and a lot of my friends were killed, at least four or five from Trinidad. I was extremely glad the war was over.’

Flight Lieutenant Ulric Cross, DSO, DFC

In Jamaica, Connie Mark, who was serving with the ATS, remembered VE Day as a marvellous time:

‘Everybody was happy ’cause as far as we were concerned, the war was finished. Everybody was happy. Everybody just jumped up and down; the war was over, and it meant that no more of our people would be killed. We had parties, and everybody took it as an excuse to have a party, a drink up, and get stone-blind drunk. I didn’t used to drink in those days; I just went to all the parties that there were. Yeah, you were glad that the war was over, and people weren’t going to die. You didn’t have troop ships coming in with people sick, or blinded, or with missing limbs.’

Connie Mark

Cerene Palmer said that everybody in Jamaica wanted to know that Hitler was really dead.

‘They wanted to make sure it was him. They hung Mussolini so everybody could see him. You knew he was dead.’

Cerene Palmer

In England, another Jamaican, Sam King, was at his RAF hangar, repairing an aircraft, when victory was announced on the tannoy. Everyone was given the remainder of the day off, but they were told they would have to be back on duty the next day. Sam put on his RAF uniform and caught the bus into Weston-super-Mare:

‘It was different. The birds were singing. I got off the bus and I was on the right-hand side of the road, passing the George and Dragon. A lady rushed out: “Come along! You must have a drink.” She pulled me in the pub and said, “Bring rum for this airman, he’s from Jamaica.” I said, “I’m very sorry. I do not drink rum.” She said, “How can you not drink rum? You’ve got Jamaica on your shoulder!” She brought the rum and I had to drink the rum. Everybody was happy. It was VE Day. There’ll be no more bombing. No more killing. And especially for the women whose loved ones were coming home. It was good to be alive and I was alive.’

Sam King

Harold Sinson, from British Guiana, served in the RAF in Pembroke Dock in Wales. When asked about his memories of VE Day, he spoke of how everyone just downed tools:

‘Everything was free – there were drinks all over the place, there was dancing in the street. It was really exciting. It lasted all that day and all night – nobody knew what was happening, you just danced away until you had enough and you went back to camp and to bed. We got off the next day – it was wonderful. We spent time with our friends, and felt very humble for the things people did for us and the people who had died.’

Harold Sinson

Eddie Martin Noble was a Jamaican who was also in the RAF and serving in England. He said he was in Cambridge on VE Day when ‘the very the end of the war in Europe was announced’. In his autobiography, published in 1984, he reflected:

‘It is almost impossible for me to adequately describe here, after all these years, the incredible scenes of joy and sheer abandonment which took place in Cambridge that day and night. Complete strangers would hug and kiss you in the streets, shops and parks. There was dancing in the streets, and bonfires everywhere. In a park near the university I saw servicemen and officers take off their tunics and throw them on a massive bonfire.’

Eddie Martin Noble in his autobiography Jamaica Airman: A Black Airman in Britain 1943 and After

Eddie acknowledged that Winston Churchill was ‘a great war leader’. He believed that, without his leadership, the British people would have lost the war, ‘But, to put it bluntly, he was a bastard. As soon as the war ended they threw him out, and let a Labour government in, so that should tell you something.’

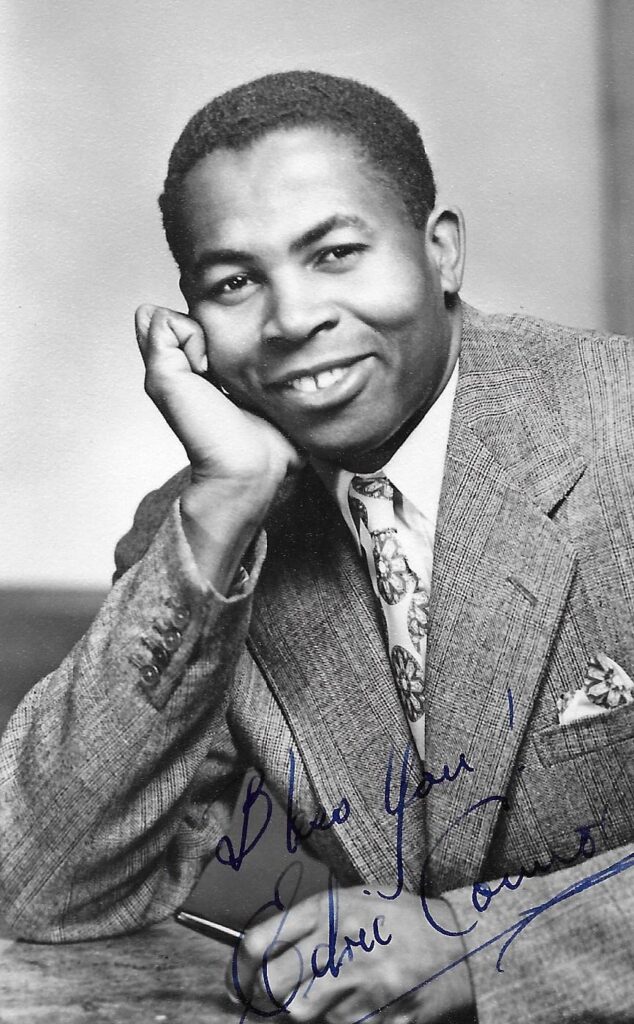

On VE Day, the Trinidadian singer Edric Connor was ready to broadcast the first instalment of a new BBC series of programmes called Serenade in Sepia. However, the live broadcast was postponed so that the BBC could do justice to the celebrations of the end of the war. It was decided that Edric and his co-star, Evelyn Dove, would record the programme on VE Day instead and it would be broadcast at a later date. However, getting to Broadcasting House on VE Day proved an almost impossible task for Edric:

‘Most public transport stopped running. Housewives left kitchens. Shops and schools were closed. All commercial and industrial activities ceased. The only way I could get to London that day was in a hearse. As I sat near the coffin I contemplated the dead body it contained. What a day to go to the BBC! Then I thought of the millions of people killed in the war and wept quietly. Somebody has to cry for the steel that is bent and the body broken against its will. Somebody has to cry for the children unborn and those born but hungry. Somebody had to cry for humanity. The hearse put me down at Oxford Circus.’

Edric Connor

Ambrose Campbell, the Nigerian musician and bandleader, was also drawn into the VE Day celebrations. On that memorable day he launched his new band, the West African Rhythm Brothers, in Trafalgar Square and Piccadilly Circus. Sixty years later, Campbell reflected:

‘Everybody had been waiting for that day so everybody was happy and jumping around and dancing and kissing each other, so we thought we’d join the celebration. Four or five drummers and two or three guitars and these voices singing. We had a huge crowd following us around Piccadilly Circus. You could hardly move.’

Ambrose Campbell

In Black London (2015), Marc Matera described Campbell’s participation in VE Day as a ‘spontaneous expression of hope for a transformed post-war social order’.

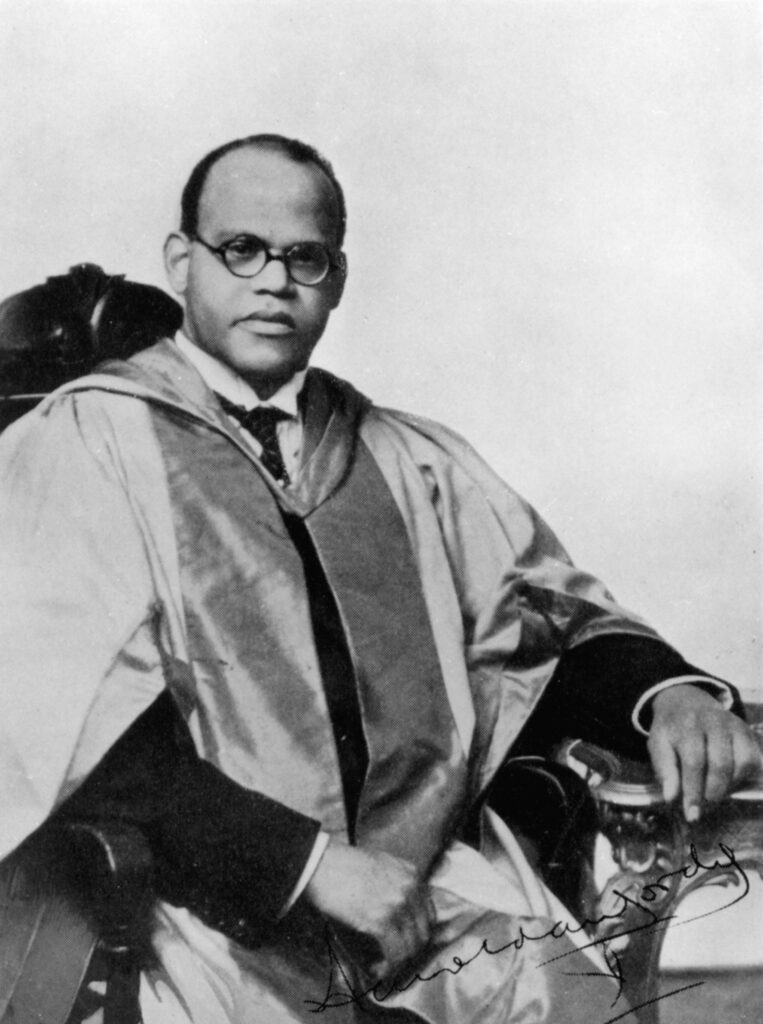

As the war drew to a close, Dr Harold Moody made a broadcast to the people of the Caribbean for the BBC’s Empire Service in their series, Calling the West Indies. Extracts were then published in the News Letter of the LCP. ‘VE Day has come and gone,’ he said:

‘The years of blood and toil and sweat have come to an end in Europe. The tension of war for millions is over. We are free, again in the continent of Europe. I have been in the midst of a peoples whose homes have been shattered, whose families have been battered, who themselves have been maimed. I have seen these people bear all these shocks bravely and with stoic resistance. I now see these same people breathing the air of relief, and, in their rejoicing, lighting those fires the sight of which, a while ago, would have struck them with terror … I have rejoiced in meeting from time to time the fine group of men and women you have sent over from the West Indies, British Guiana and British Honduras. Their doings and achievements have thrilled me beyond telling. They will be coming back to you, we hope, before very long now, just as I hope my five boys and girls in the services will be back again soon. They have all done magnificently as they battled against evil things. Now they and you will have to continue the war against those evil things which are hindering the progress and development of our beloved lands in the West Indies.’

Dr Harold Moody

On 24 April 1947, at the age of 64, Dr Moody died of acute influenza at his home in Peckham. Thousands of people from all walks of life, including many of his patients, paid their respects at his funeral service which was held at the Camberwell Green Congregational Church. In his biography of Dr Moody, David A. Vaughan said that Moody gave to the LCP ‘devotion, sacrifice, passion and zeal for the rest of his life and he held the office of President continuously until his death in 1947’. Sam Morris commented, ‘In his passing, the black people then resident in Britain lost a sound, sincere, dedicated but completely unpretentious champion.’

Pauline Henebery remembered the feeling of relief when the war in Europe was over, but it was short-lived for her because of the shock of what happened to Hiroshima, a city in Japan that was largely destroyed by an atomic bomb on 6 August 1945. Between 70,000 and 126,000 civilians were killed. She said:

‘I remember the news of that, and was just shattered by the horror, and what it was going to mean. It was just so, so awful. I had the most terrible feeling of guilt that this nation which I’d adopted had done this … well, it was the Americans, really, but still.’

Pauline Henebery

Baron Baker, a Jamaican who had joined the RAF in 1944, felt passionately about the role West Indian servicemen had played in the conflict, as well as the sacrifices some of them had made for the mother country:

‘Many of our blue blood blacks died for the establishment. I know it because I buried several … so many of our young Jamaicans, and West Indians, contributed immensely to Britain’s war effort. It should be remembered at all times. It should never be forgotten.’

Baron Baker

At the end of the war, Esther Bruce took Stephen Bourne’s mother Kathy, aged 14, to see St Paul’s Cathedral. Like so many others, Esther found it hard to believe that St Paul’s had survived the German bombardment of London (the Blitz, doodlebugs and V-2 rockets). For many, including Esther, the beautiful and majestic cathedral symbolised the hope and strength of the British people. ‘Look at St. Paul’s Cathedral,’ Esther said to Kathy. ‘There’s not a mark on it. We’re lucky. We’ve still got half a street, but some poor souls have ended up with nothing.’

Extracted from Under Fire: Black Britain in Wartime 1939–45 by Stephen Bourne

Books related to this article