3rd March, 2025 in Biography & Memoir, History, Society & Culture, Women in History

By Jane Dismore

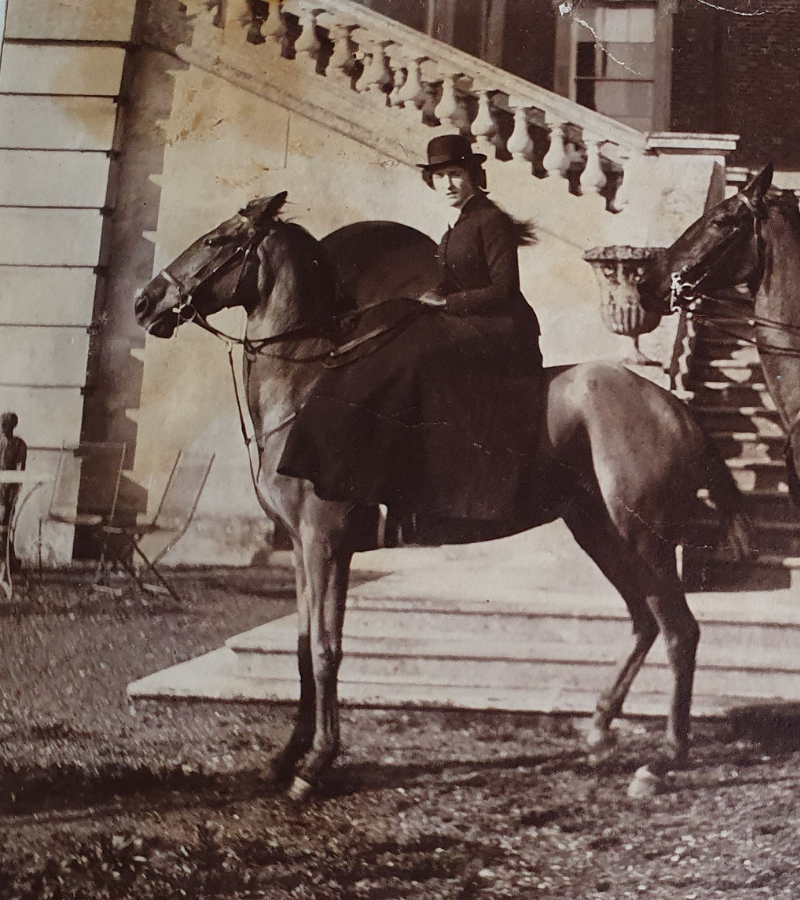

At her birth in 1889, Miss Dorothy Walpole, as she then was, seemed to have it all. Her family boasted an impressive political and literary heritage: ancestors included Sir Robert Walpole, Britain’s first Prime Minister and his famed son, Horace, author of the first gothic novel. Her father was heir to an earldom and her American mother the daughter of a wealthy railroad magnate. Dolly (as she was known) was raised in two of Norfolk’s finest houses, Wolterton and Mannington. But her privilege was tempered by several factors, including the early death of her mother and the clear desire of her father for a male heir.

When Dolly married a clever but poor army officer, Captain Arthur Mills, her father – by then the Earl of Orford – disinherited her and went on to marry a woman younger than his daughter. Life is often described as a journey. As an aristocratic woman with all the attendant advantages, Dolly could have taken the easy route, but the consequences of falling in love with the ‘wrong’ man saw her take another path. In doing so she underwent a metamorphosis and discovered much about herself, physically and mentally. Although she would never lose her love of donning a glamorous frock and downing a cocktail, for several months each year she left the decadent glamour of Jazz Age London for the wildness of desert, jungle and bush, where she found great solace.

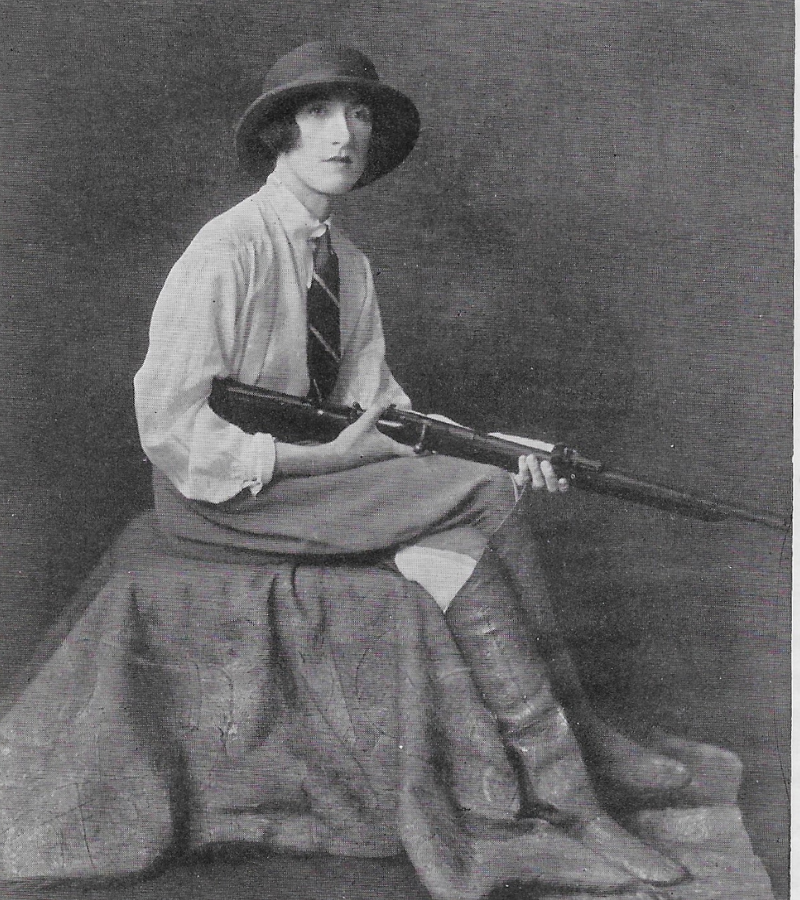

Dolly had fallen in love with the Sahara when holidaying in Algeria. Her first expedition was in 1922 to Tunisia, to stay with the reclusive cave dwellers. Before Dolly, few women had chosen to journey through Africa, much of which was still little-known, and she became particularly known for her exploration in West Africa, becoming the first English woman in Timbuktu. Chugging along sluggish rivers on rickety boats she endured deadly heat, man-eating crocodiles and a male pursuer with teeth filed to sharp points. That achievement and the first of her six travel books, The Road to Timbuktu, cemented her reputation as an explorer and a travel writer.

In Liberia she was the first woman to cross the country to its furthest point, encountering cannibals on the way. In Venezuela she travelled over 800 miles through challenging terrain and along the Orinoco river. Everywhere she went, she stayed with local tribes whenever possible. Those who accompanied her on her expeditions were people she hired locally as guides, porters, interpreters. She never travelled with close companions, not even Arthur, who undertook his own journeys to find material for the successful adventure stories he wrote. They would reunite in their London flat, holiday together, then write and socialise.

Dolly travelled during a volatile period, when the world was emerging from the chaos of the Great War and re-shaping itself politically and culturally. She witnessed history in the making when Lord Balfour opened the first Hebrew University in Tel Aviv: her observations of the relationship between Jews and Arabs were prescient. In Iraq, she stayed with the Yezidi tribe, arriving via Aleppo in northern Syria and enduring a near-ambush by brigands. A century later, it is sobering to see that parts of the Middle East into which she ventured remain deeply troubled, and that some other places and peoples she wrote about have, at various times, continued to be the subject of distressing news.

Afterwards she shared her experiences with the world by turning them into compelling prose for her travel books and escapist stories for her novels, while undoubtedly being the only explorer who also wrote journalistic features on a wide range of topics for the emerging modern woman, now empowered by achieving suffrage. That she continued to enjoy the buzz of a social life when back in England provided a marked contrast with the other worlds she inhabited.

Today we take for granted the protection of inoculations for foreign travel. In Dolly’s time, smallpox, malaria and TB were rife, the number of people killed between 1900 and 1950 alone totalling more than those killed in both world wars. In several countries she explored, yellow fever was a killer: inoculation trials did not begin until 1938. Although she took precautions against certain illnesses, she succumbed several times yet survived, her petite, almost delicate frame enduring an extraordinary amount: no doubt she put her resilience down to the cigarettes she smoked and the alcohol she consumed whenever the opportunity presented itself.

Yet she also faced personal tribulations, including – ironically – a serious accident back home in London when she was at the height of her fame, and an emotional blow from her father. But she was buoyed up by her election in 1930 as an early female Fellow of the Royal Geographical Society (RGS). Always keen to foster a curious mind in the young, on her death in 1959 her most significant bequest was a legacy for a young woman member of the RGS to use for an explorative enterprise.

With no-one close enough to keep her memory alive, Dolly has been overlooked. Yet her curiosity, courage and sense of humanity showed the world extraordinary places and peoples, focusing always on what draws us together rather than what divides us.

Books related to this article